5,000 Hours in the Making: A Bible in Korean Calligraphy

Long before daybreak, at 4:00 a.m., Jung Choe makes his way to a quiet corner of his home in Tacoma, Washington. He sits at a table and turns on a light that shines upward through the glass surface. Opening his Agape Big Letter Korean Bible, he lays a sheet of rice paper in front of him so it is illuminated by the light beneath. Slowly and carefully he begins to copy the text in Korean calligraphy, an ancient style of writing renowned for its beauty, elegance, and precision. The Bible, for him, is a source of daily nourishment. Alone with the text, he works in prayerful meditation for several hours, word by word, line by line, until the sun rises and the new day begins.

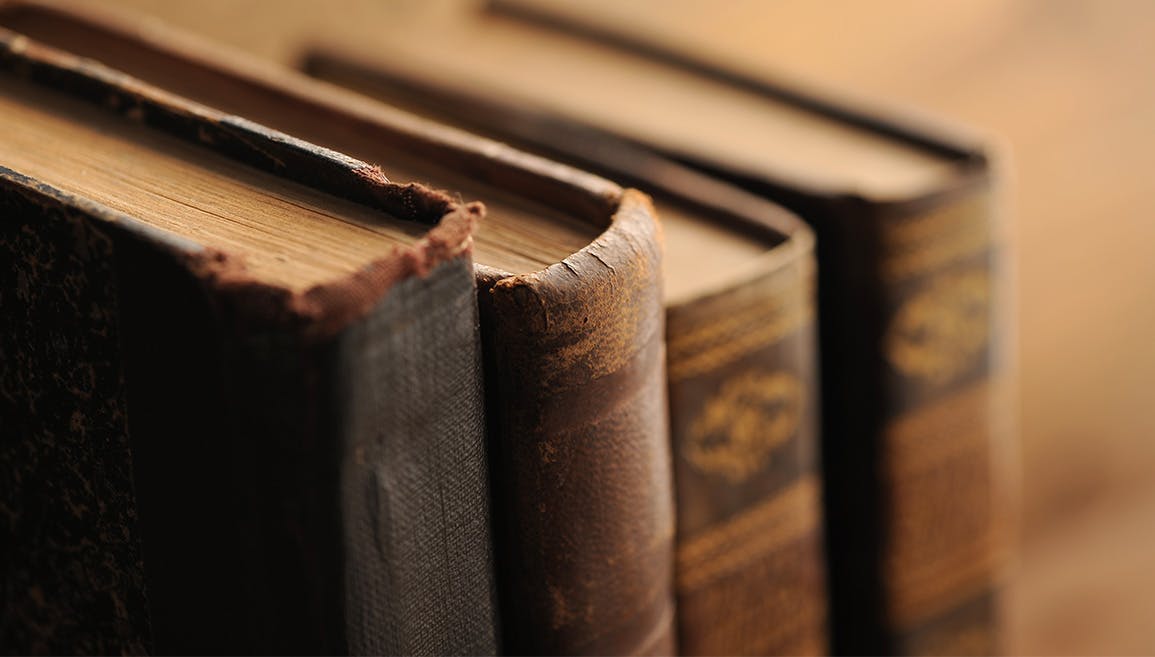

Figure 1: A sample of Jung Choe's work. The pages are open to the Gospel of John, chapter 3. The right page starts with the second half of verse 18 and the left page concludes with the first half of verse 22. Korean is read right to left, top to bottom. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Jung was born in Korea in 1944. He received little formal education, finishing only middle school. His father was a farmer and soon enough Jung entered the profession as well, eventually marrying and starting a family. After his sister immigrated to the United States, finding a new home in Washington state, he too began to dream of a better life in America. On January 1, 1983, he and his family took a leap of faith and moved to Tacoma. There, Jung and his wife would raise their three children as he earned a living as a janitor and maintenance worker.

Around 1986, while browsing a local store, Jung stumbled upon a Bible printed in Korean calligraphy. The book spoke to him. He had only recently become a Christian, joining the Tacoma First Baptist Church, a predominantly Korean church near his home. He had long been fascinated by Korean calligraphy, an art that had been part of Korean culture for more than 2,000 years. While he had learned some techniques as a child, as he grew older, he had little time to pursue that passion. Now, living in a new land and practicing a new faith, he challenged himself to learn Korean calligraphy and one day create a Bible of his own.

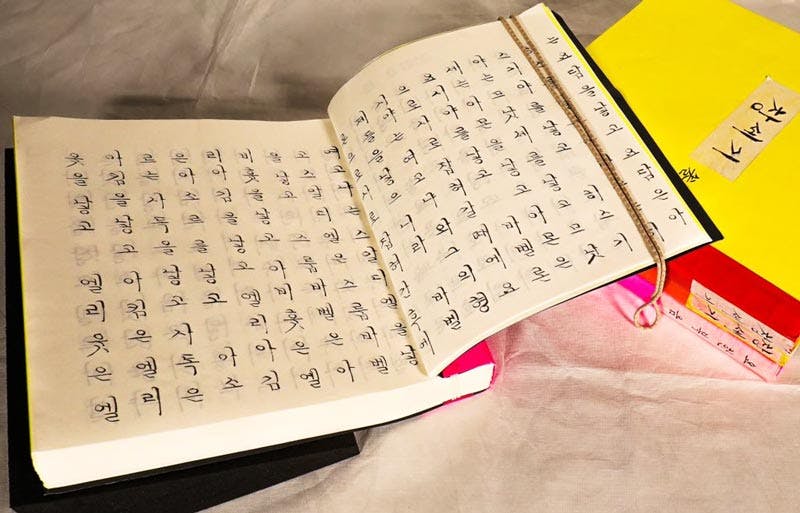

Over the next 14 years, Jung honed his skills through daily practice. He finally began his project in 2000. His son, Kyle, who had just completed medical school, supplied the special rice paper Korean calligraphers traditionally used. The work is time-consuming, requiring immense concentration and meticulous care. However, it is also devotional, allowing him to engage the text with a sharp focus. On good days, after several hours, Jung could write half a chapter. He finished the last chapter in 2009. The Bible is bound into 50 volumes, with 25 chapters in each. It took him roughly 5,000 hours. Jung felt an overwhelming sense of achievement, like a mountain climber who finally reaches the summit. As a token of gratitude, he donated the Bible to his church.

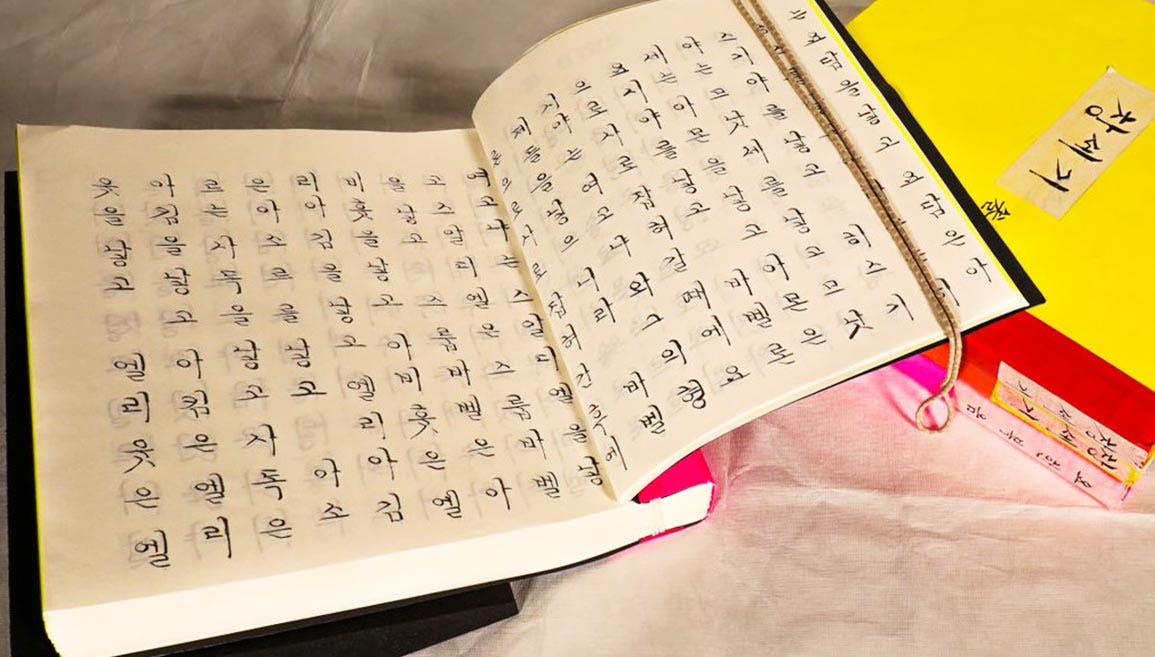

Figure 2: The open book is the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 1, verses 9–14. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Almost immediately, Jung began work on a second copy, which he completed in 2017 and gave to his son, Kyle. Jung turned his attention to a third copy in 2018. As he neared completion in 2021, Kyle contacted Museum of the Bible on behalf of his father, offering to donate this one to the museum. In March 2022, Jung and more than a dozen family members came to Washington, DC, to present this Bible to the museum, where it has found a home in the permanent collections.

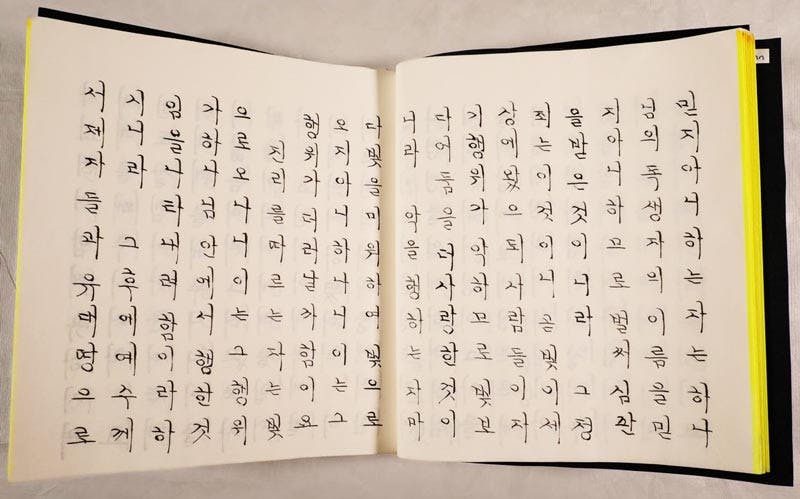

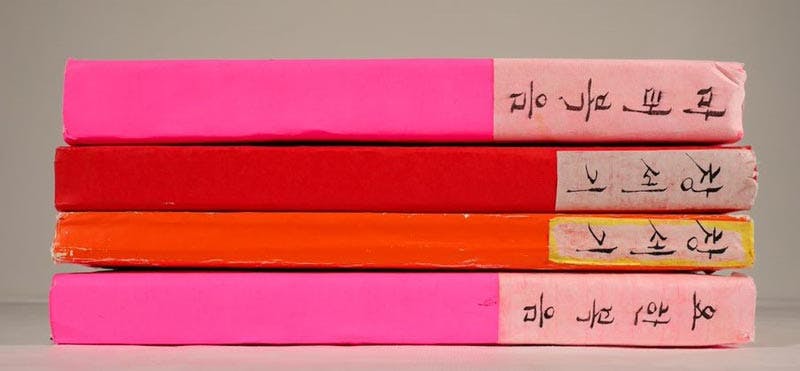

Figure 3: The top book is the Gospel of Matthew. The two middle volumes are the book of Genesis. The book on the bottom is the Gospel of John. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Museum of the Bible was both thrilled and humbled by Jung’s generous gift. His story is unique in many ways. Yet in other ways, it is similar to the stories of hard work and sacrifice, love and hope, and courage and faith that have defined the lives of millions of immigrants who have come to this country, yesterday and today. Jung’s handwritten Bibles form a bridge between his life in South Korea and America. The museum’s copy will be placed on display in a section on the Bible and immigrant communities in our permanent exhibition, The Bible in America, later this year.

Figure 4: All 50 volumes of Jung Choe's Bible in Korean calligraphy. Photo copyright Museum of the Bible 2022.

Jung, according to Kyle, has already started on copy number four.

By Dr. Anthony Schmidt, Director of Collections and Curatorial