Hope amidst Despair: The Prophets by Jacob Barosin

“My Bible illustrations in later years had their roots and starting point in this Montmejean twilight zone.”

— Jacob Barosin, from A Remnant

The sun shines through the upper-story windows of a little schoolhouse in Montméjean, France. Jacob and Sonia lie still on a bed, listening to children reciting their lessons on the ground floor. They suppress the urge to move so the bed won’t squeak and ignore the desire to get up and walk so the floorboards won’t creak. Spread open between them is a Bible, from which they both silently read, passing the hours until night falls, when the building is empty and they can eat and move around again. The next morning, the schoolteacher arrives early to bring them food and water, and the cycle starts all over. This was their routine.

This was but one of many harrowing moments in the lives of the Barosins as they fled Nazi persecution and detention at Nazi concentration camps for more than a decade. The horrors of the Holocaust, the systematic murder of nine million humans that specifically targeted six million Jews, would affect Jacob and Sonia’s lives forever. But their story of survival also includes the sources of comfort they found along the way. One of those sources was the Bible. Its influence on Jacob Barosin’s subsequent art, seen through a series of the Hebrew prophets, is the subject of a current exhibit at Museum of the Bible. The exhibit explores the hope Jacob found in the words of the Hebrew prophets, showing that even in times of despair hope can be found in the pages of the Bible.

HOW IT BEGAN

Jacob and Sonia spent years on the run. They started in 1933, when Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. His increasing oppression of Jews forced Jacob and Sonia, both Jewish, to leave their home in Berlin and relocate to Paris. They lived as stateless foreigners in France until 1940, when the Nazis invaded.

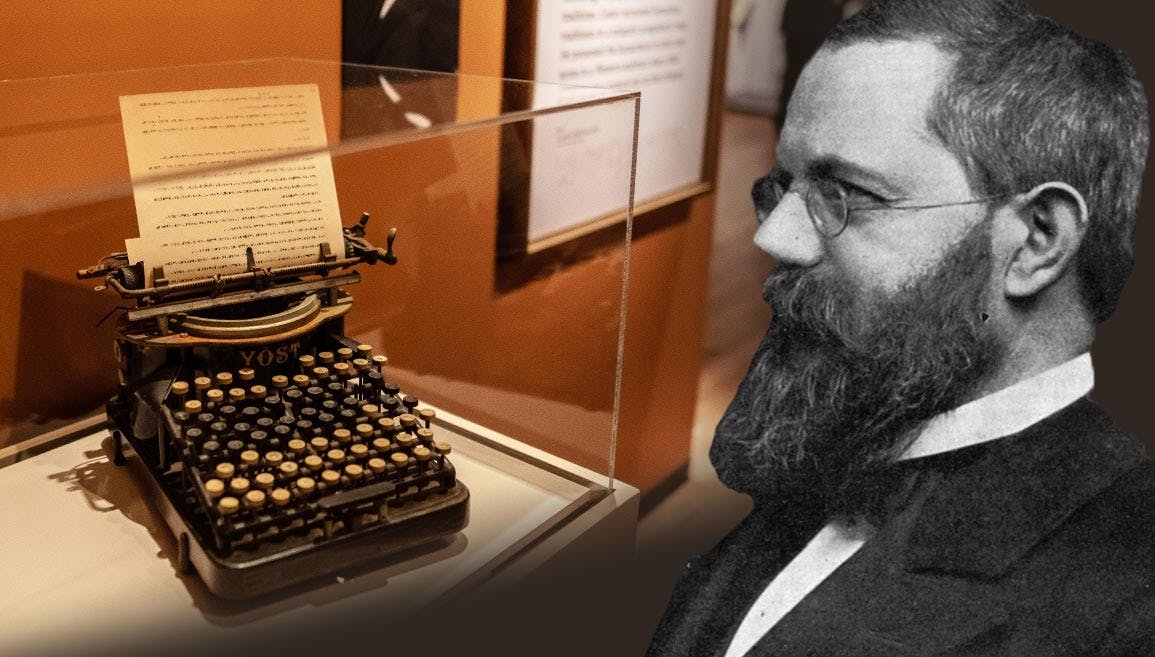

Self-Portrait

Jacob Barosin

Oil on canvas

1940s

Barosin’s personal style exhibits an affinity for post-impressionist colors and evident brush strokes but stays within the boundaries of realism. In interviews later in life, he stated he preferred his subjects to be obvious and thus leaned toward realism.

Portrait of Sonia Barosin

Jacob Barosin

Watercolor on paper

1950s

Sonia Barosin (née Finkel) met Jacob at the University of Berlin when he accompanied her violin music on the piano. She survived the Holocaust and moved to New York with Jacob in 1947.

JACOB AND SONIA ARRESTED

On May 18, 1940, Jacob and Sonia were arrested at their home in Paris. Jacob was sent to a forced labor camp in Langlade. Sonia was taken to Gurs Concentration Camp, where she stayed for 18 days until Jacob was able to get her transferred to Langlade, and then to Nice. Jacob remained in Langlade for a year but used his artistic talent to sell paintings for the National Aid Society, thus avoiding being sent to forced labor in the salt mines.

TRANSFER TO LUNEL

On May 15, 1941, Jacob was released from Langlade and transferred to Lunel by forging transfer papers. In April 1942, Sonia joined Jacob in Lunel.

AGDE CONCENTRATION CAMP

In October 1942, Jacob was “invited” to Agde Concentration Camp. A series of what seemed to be miracles allowed for his release in just one day. First, Sonia met and became friends with Mrs. Toureille, the wife of a local Christian pastor. Second, Jacob and Sonia saw Mrs. Toureille in an alley the day Jacob received his summons. Third, Mrs. Toureille told her husband about the situation prompting him to write a letter on Jacob’s behalf to Mr. Baumann, an office worker at Agde. And fourth, Mr. Baumann knew Jacob’s father and had done business with him in the past. Because of these events, Jacob was processed at Agde and released the same day.

TRANSFER TO FLORAC

Afterward, Jacob and Sonia decided to relocate and left for the mountain village of Florac. A local man named E. Audrix gave them a place to live and assured them he and his wife would do all they could to protect them. However, on February 17, 1943, Jacob was arrested in Florac and sent to Gurs Concentration Camp. Sonia remained hidden at Audrix’s house.

GURS CONCENTRATION CAMP

Jacob spent five weeks at Gurs. Many men in his barracks were “called up,” meaning they were sent to Auschwitz and Dachau. During his time, he kept a diary with notes and sketches of the people he lived with and the horrors he witnessed. Many of the people he sketched remain unidentified. This diary is now at Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, Israel.

In the Valley of Death

Jacob Barosin

Pen and ink on paper

1940s

In this striking drawing, Barosin depicts the biblical figure of David walking through a literal “valley of death,” surrounded by the emaciated and skeletal figures of Jewish prisoners in striped uniforms from the Gurs Concentration Camp, where Barosin was held for five weeks during World War II.

HIDING IN MONTMÉJEAN

On March 21, 1943, Jacob was released from Gurs and sent to a forced labor camp in Gignac. He managed to escape with the help of fellow internee George Romano and reunite with Sonia at Audrix’s house in Florac. Recognizing the danger, they relocated again to the village of Montméjean and hid on the upper floor of a small schoolhouse, depicted below.

The Schoolhouse in Montméjean

Jacob Barosin

1940s

This pen-and-ink drawing depicts the upper room of the schoolhouse where Jacob and Sonia hid from the Nazis.

The Bible they read was given to them by the Christian schoolteacher, Simone Serriere, who said to them, “You will have plenty of time now. There is a book which my father, Pastor Baldy, bought as a young man many years ago. It might be the right book for you at the present time.” And it was. As Jacob lay there, day after day, reading from this Bible, he was inspired by the stories of the prophets, whose timeless message of hope amidst despair brought him solace. Later, he remarked on his time, saying, “I had read the Bible in my teens. I have never understood it as I understand it now. . . . My understanding was a grasping of a revealed reality. It may be that the utter helplessness and the dangerous situation in which I found myself for years now gave me an inkling of what Jeremiah [30:10] meant:

‘Therefore fear you not, O Jacob

My servant, saith the Lord,

Neither be dismayed, O Israel;

For lo, I will save thee from afar,

And thy seed from the land of their captivity.

And Jacob shall again be quiet and at ease.

And none shall make him afraid.’”

DISCOVERY IN MONTMÉJEAN

After four months of hiding, Jacob and Sonia were discovered in the schoolhouse after Jacob emptied their toilet bucket into the cellar and onto a young couple who thought they had found a quiet spot to be alone. The townspeople of Montméjean were told the Barosins were French defectors, not Jews, and agreed to keep quiet, but the Barosins decided to relocate again to Soisy, a suburb of Paris, and hide with Sonia’s cousin Boris and his family. They were all hidden by Boris’s French mother-in-law in the garden shed located on her property. For nearly a year, they shared that small space, never going out into the streets.

RETURN TO PARIS

On June 6, 1944, America invaded Nazi-occupied France at Normandy and liberated Paris on August 24. After four years of running, Jacob and Sonia returned to their Paris home.

FROM PARIS TO NEW YORK

Jacob and Sonia lived in Paris for three more years before moving to the United States in 1947. They settled in New York, where Jacob made a living as an artist receiving commissions and working as an illustrator for NBC-TV.

Self-Portrait

Jacob Barosin

Oil on canvas

1950s

In this self-portrait, Barosin depicts himself in his home in New York. His style is still evident through the bold colors and obvious brush strokes that maintain a realistic subject and setting.

PAINTING THE PROPHETS

It was during this time that Jacob painted a series of 18 life-size portraits of the prophets inspired by his reading of the Bible while in hiding. These are now part of the permanent collection at Museum of the Bible. Jacob describes the series in this way, “My 18 over life-size prophets . . . I did on my own, so to speak, because they touched the central issue of my heritage. Free from any interference from publishers and art directors, I could say in these works what I wanted to say and the way I wanted to say it” (as quoted by Helen Groninger in Church Management magazine, June 1955).

Amos

Jacob Barosin

Late 1940s–early 1950s

Oil on canvas

Isaiah

Jacob Barosin

Late 1940s–early 1950s

Oil on canvas

Jacob’s series on the prophets, and other works by him, have been donated by his family to Museum of the Bible’s permanent collections and are currently on exhibit until July 9, 2024.

Hope amidst Despair: The Prophets by Jacob Barosin is included with general admission. Learn more and get tickets today.

You can also see Barosin’s life-size paintings of the prophets on our Collections page.

“Do not despair, do not give up as we, preceding generations, never gave up. Fight for your survival the best way you can. The main thing is to stay alive — as a partisan in the Russian woods, as a hungry stateless man under police surveillance, as a persecuted Jew in hiding, whatever your style and your choice and your opportunity, stay alive. ‘Into the storm and through the storm,’ as Churchill said. And if you stay alive, you will see the day when you can cry out: there is beauty in the world, there is truth and there is freedom.”

— Jacob Barosin, from A Remnant

קדוש השם (kiddush hashem)

Sanctifying the Name (Martyrdom)

Jacob Barosin

Pencil on paper

1980s

This remarkable drawing by Barosin depicts the many faces of the Holocaust, including his young sister in the bottom right corner.

By Amy Van Dyke, Lead Curator of Art and Exhibitions