The Speculum humanae salvationis

Here begins the proem of a certain new compilation

Whose name or title is the Mirror of Human Salvation.[1]

The Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation) was a popular religious text in late medieval Europe. It belongs to the rich literary genre of medieval specula (mirrors)—texts that invite readers to cast their gaze upon a specific topic, ranging from the church or monasticism to astrology or the life of a prince. Composed as a lengthy poem, the Speculum examines the biblical narrative of redemption. Like many popular medieval texts, the Speculum includes rich illustrations to help poorly educated or even illiterate audiences follow along. Echoing Augustine’s call to know God and know oneself, the anonymous author writes, “And in the present life I think nothing to be more profitable for man than to know his creator and his own condition. The literate can learn this condition from the written words, but the illiterate should be taught by the books of the laity, that is, in pictures.”[2]

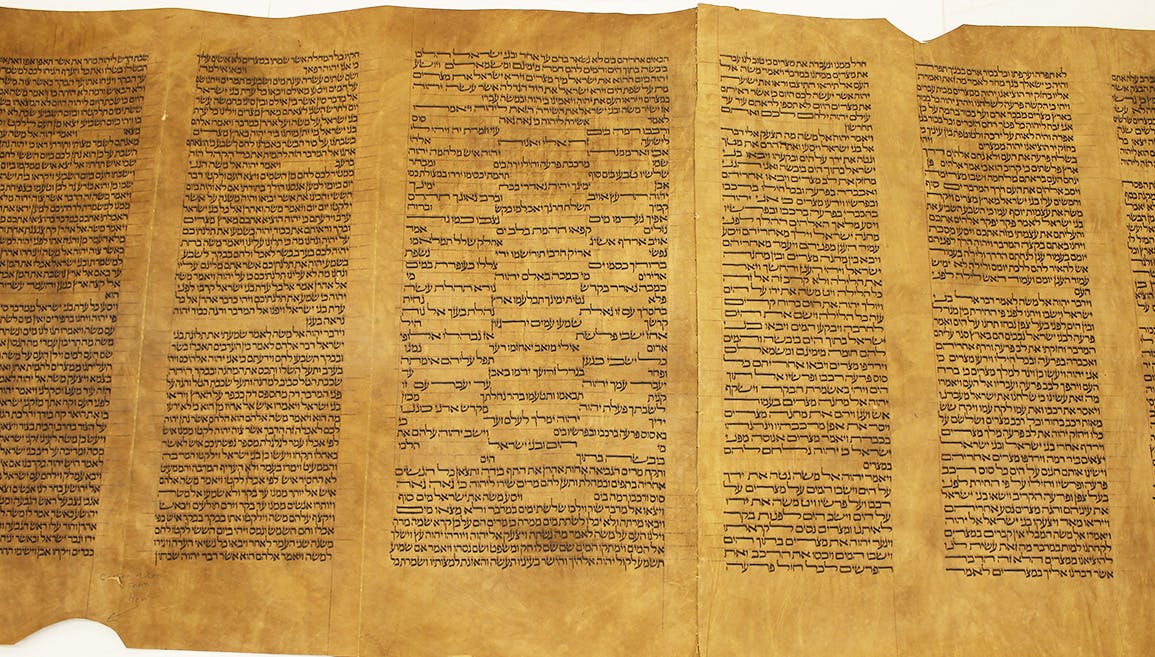

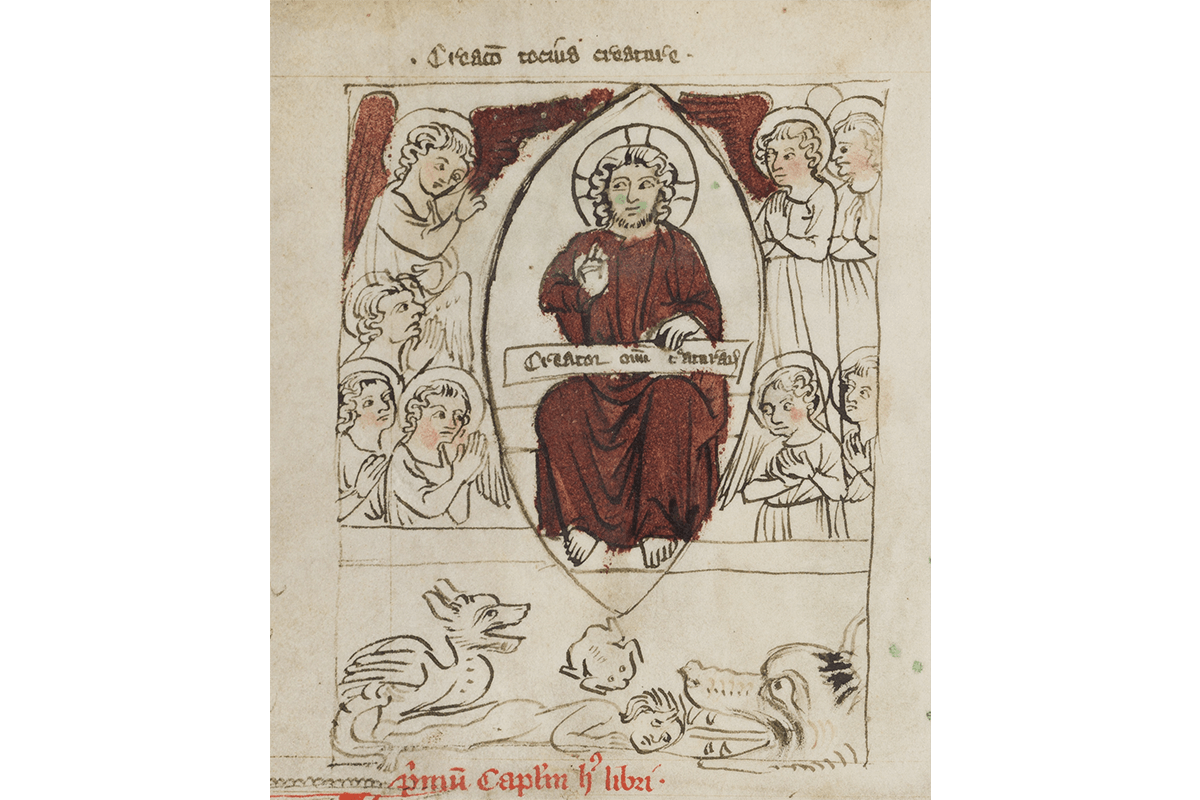

Figure 1: Museum of the Bible’s manuscript of the Speculum (MS.000321) features 192 pen-and-ink illuminations, likely by Konrad von Tiergarten, an Italian court painter to Leopold III, Duke of Austria. This opening illustration depicts God, surrounded by the angelic host, casting Lucifer out of the heavenly court. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.[3]

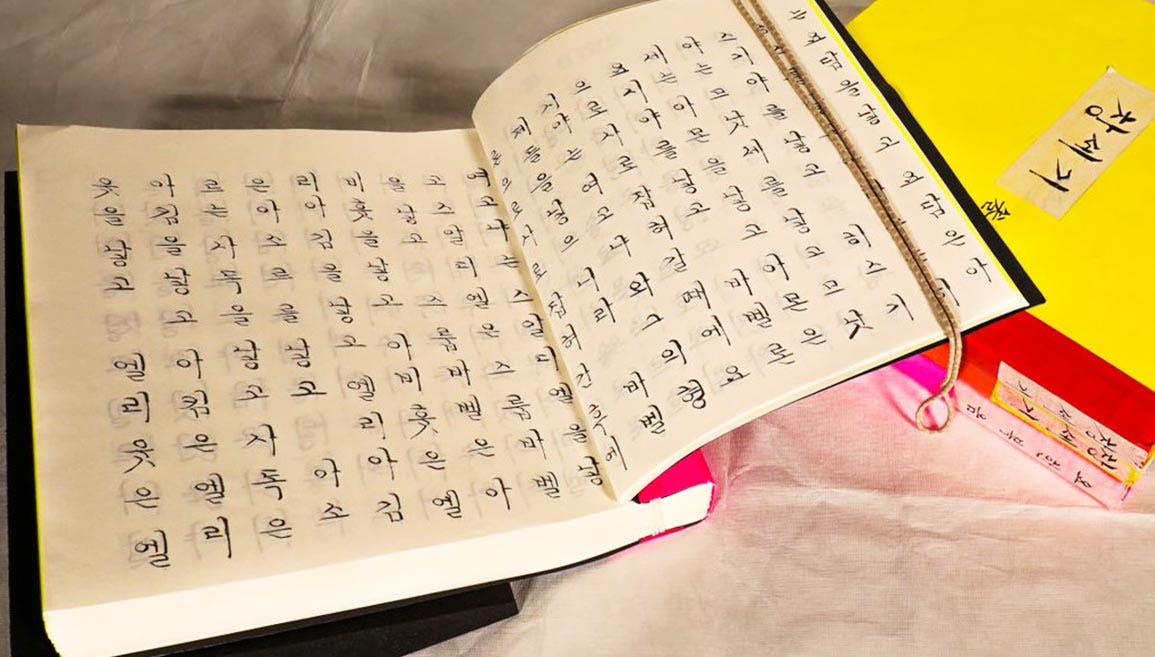

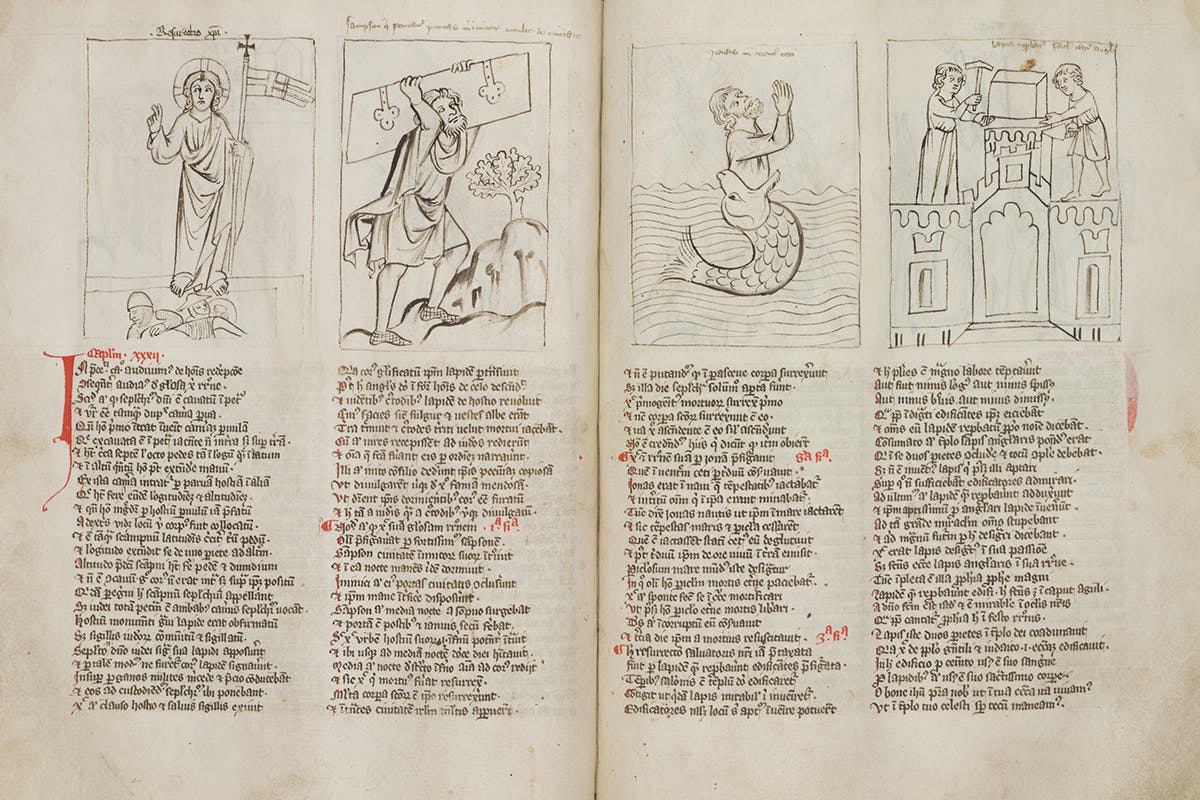

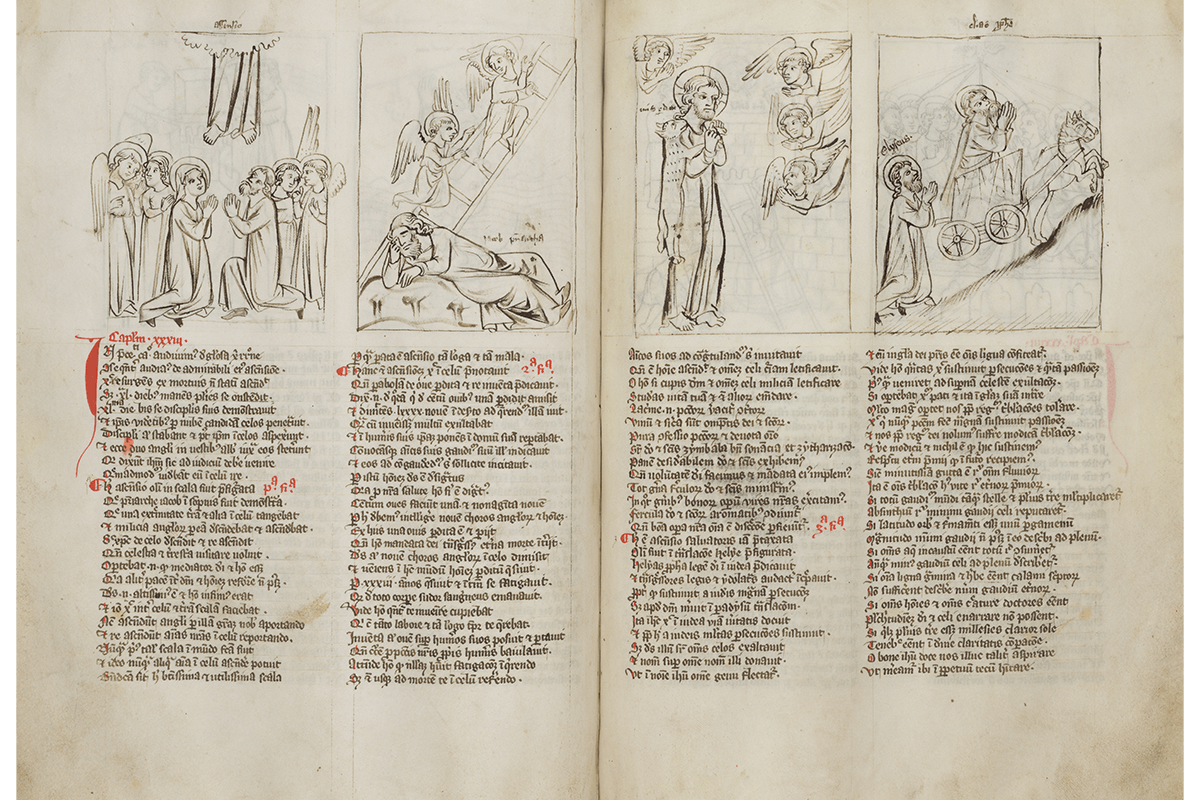

The Speculum presents the biblical narrative of redemption typologically. Typology, a popular method of biblical interpretation in medieval Europe, highlights people and events in the Old Testament that prefigure (or serve as “types” of) Christ and the events of the New Testament. The text follows a distinct pattern, examining one New Testament event and three earlier events that prefigure it, with an illustration accompanying each of these events. For instance, in the chapter on Jesus’s resurrection, the author highlights three typological events that foreshadow his victory over death: Samson escaping with the gates of Gaza (Judges 16:1–3), Jonah emerging from the belly of the whale (Jonah 2:10), and the stone rejected by the builders becoming the cornerstone (Psalm 118:22–23).

Figure 2: Illustrations from left to right: The resurrection of Jesus, Samson carrying the gates of Gaza, Jonah emerging from the stomach of the whale, and builders laying the cornerstone. Folios 35v–36r. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.[4]

In Judges 16, Samson enters the hostile city of Gaza, and his enemies prepare an ambush while he sleeps. Samson escapes unharmed by tearing the city gates off their hinges and carrying them away. Earlier Christian commentators identified this with Christ’s descent into hell (the city of his enemies) and subsequent resurrection, and the Speculum follows suit. The next two types—Jonah and the cornerstone—were identified by Jesus himself. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says to the scribes and Pharisees, “An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40). And in Matthew 21:42, Mark 12:10–11, and Luke 20:17, Jesus identifies himself as the stone rejected by the builders which has now become the cornerstone. The Speculum concludes,

Christ was the stone, marked out in his passion,

but became the cornerstone of the church in his resurrection . . .

That stone joined two walls of the temple of God

because Christ built one church from both the Gentiles and Jews

In this building, he used his own blood instead of cement,

and he used his most holy body in place of stones.

O good Jesus, grant to us that we may so live in your church

that we may abide in your celestial temple above with you.[5]

Other chapters follow a similar pattern. In the chapter on the ascension of Christ, the Speculum discusses Jacob’s ladder (Genesis 28), Elisha’s ascent to heaven (2 Kings 2), and the parable of the lost sheep (Matthew 18 and Luke 15).

Figure 3: Illustrations from left to right: The ascension of Christ, Jacob’s ladder, the parable of the lost sheep, and the ascension of Elisha. Folios 36v–37r. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.[6]

Elaborating upon the parallel between Jacob’s ladder and Christ’s ascension, the author writes,

This ascension formerly had been prefigured in the ladder

which had been shown in dreams to the patriarch Jacob.

One end of it was touching the earth and the other heaven,

and a host of angels were descending and ascending on it.

So Christ descended from heaven and ascended again,

when he wanted to visit heavenly and earthly places.

For it was fitting that he be God’s mediator and a man,

since otherwise he would not be able to renew the peace between God and man.

For God is highest and man was lowest,

and therefore Christ made a ladder between heaven and earth.

Now the angels descend by it to carry grace to us,

and they ascend it again to carry our souls into heaven.

Never before was such a ladder made in the world,

and therefore no soul was ever able to ascend into heaven.[7]

Similarly, like Elisha, who preached in Judea and was “removed into paradise,” Jesus taught in Judea and “God exalted him above all heavens.” And like the shepherd who left his flock to search for one lost sheep, Christ left the heavens to search for “lost mankind,” and one day, he will carry his sheep home with him. (As this example demonstrates, the boundary between typology and analogy was often ambiguous, and not every type was drawn from the Old Testament. Types could be found in the New Testament as well.) Ultimately, the author uses these examples to exhort readers to endurance in the Christian life.

Behold, man, how great the persecutions and how great the passion Christ withstood

before he came to his heavenly, celestial exultation.

If it was fitting for Christ to suffer and thus enter into his glory

how much more fitting should it be for us to endure tribulations for the kingdom’s sake?. . .

O good Jesus, teach us to desire to reach to that place,

so that we may worthily dwell there with you eternally.[8]

For several centuries, the popularity of the Speculum was matched by only a few competitors—some of which, like the Biblia pauperum, also focused on biblical typology. The mixture of images and illustrations appealed to a wide range of readers, and the content was compelling yet comprehensible. It was translated into many languages, including English, German, French, and Dutch. It was copied by hand as a manuscript—over 400 manuscript copies survive today—and later printed as both a block book (an early form of printing that involved carving the text into a block of wood) and an incunable (a book printed with movable type on the earliest printing presses).

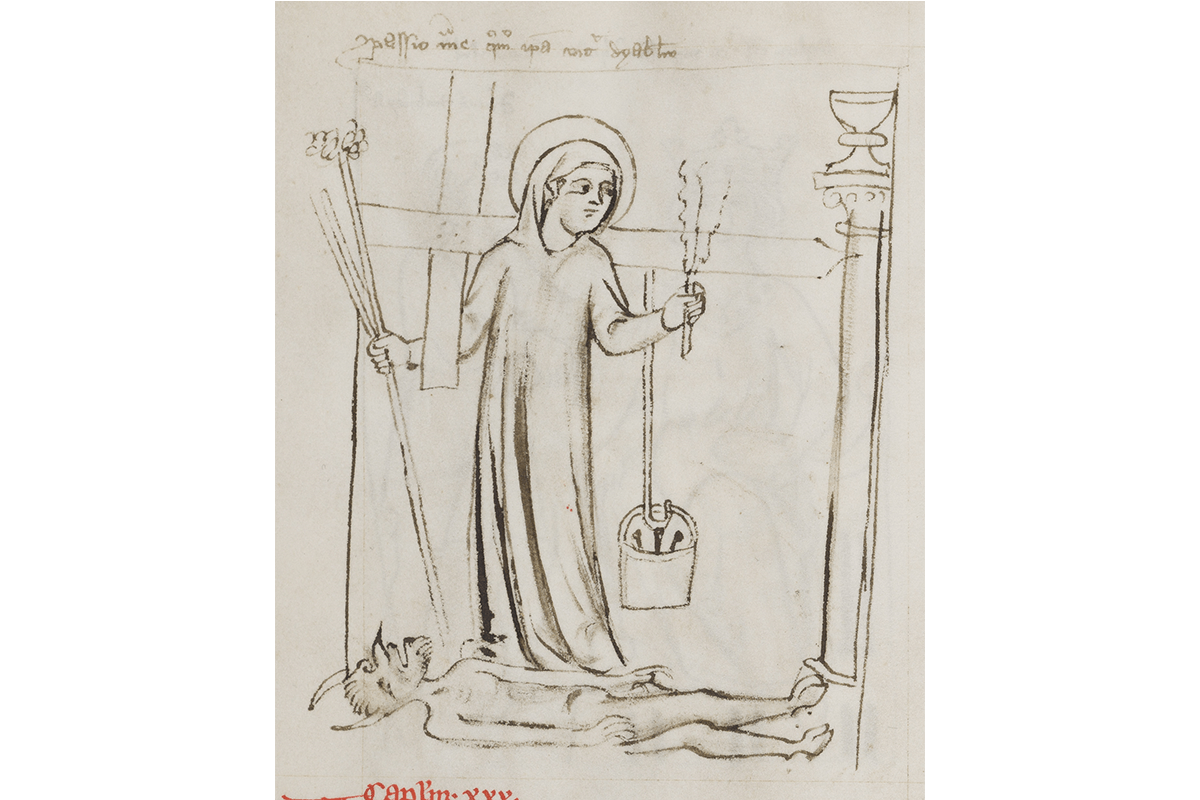

In the sixteenth century, though, the Speculum fell out of favor as quickly as it had risen to prominence, due largely to the challenges of the Protestant Reformation. Although many Protestants—particularly the Reformed church—embraced and even expanded upon the idea of biblical typology, there were aspects of the Speculum that were incompatible with Protestant theology. The Speculum touches upon many controversial theological issues—for instance, the Eucharist—but its fatal flaw in Protestant eyes was its Mariology. The Speculum devotes nearly as much space to Mary as it does to Jesus, and it speaks of Mary with language that Protestants did not accept. The author writes,

And our mother, as it were, delivered us from our adversary.

For all that Christ endured through his manifold passion,

these things Mary his mother endured through her earthly suffering.

Therefore just as Christ conquered the devil through his passion,

so Mary conquered him through her maternal compassion.[9]

Mary, the Speculum claims, has thus become an “intercessor” and “intermediary” who “reconciles sinners to God” and “softens his wrath.”[10] Protestants, with their distaste for the Catholic system of saints and intercession, would not speak of Mary this way.

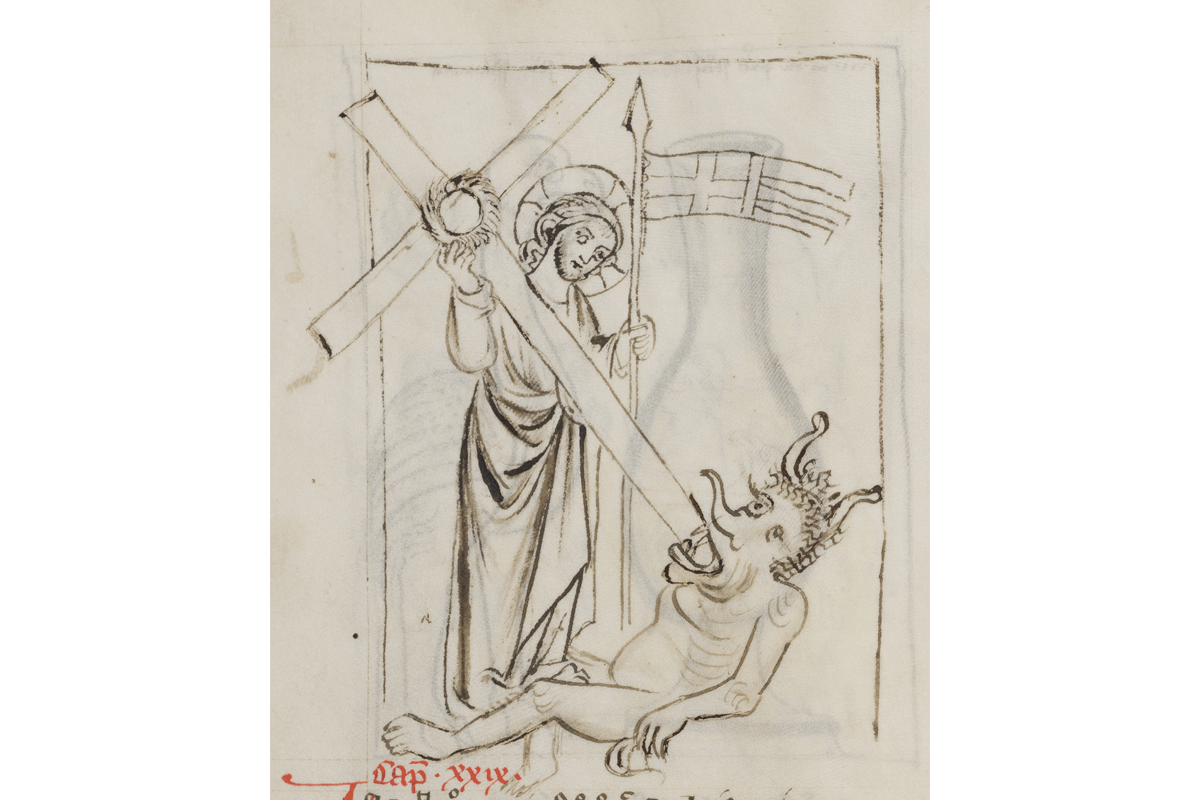

Moreover, it is often Mary, rather than Jesus, who serves as the “antitype” which various Old Testament “types” foreshadow. It was not uncommon to discuss “types” that point toward someone other than Jesus. Jesus himself describes Elijah as a “type” of John the Baptist in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 11:14). But the Speculum applies “types” to Mary that were explicitly messianic and, in Protestant eyes, applicable only to Jesus. It describes Mary as the new temple (while Christ identifies himself as the new temple in John 2:19–22 and Mark 14:57–58). It claims Mary crushed the lion and the dragon (a reference to Psalm 91:13, a messianic psalm applied to Christ in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke) and declares she has bruised the head of the serpent (a reference to the protoevangelium in Genesis 3:15).[11]

Figure 4: Christ conquering the devil. Folio 32v. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.

Figure 5: Mary conquering the devil. Folio 33v. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.[12]

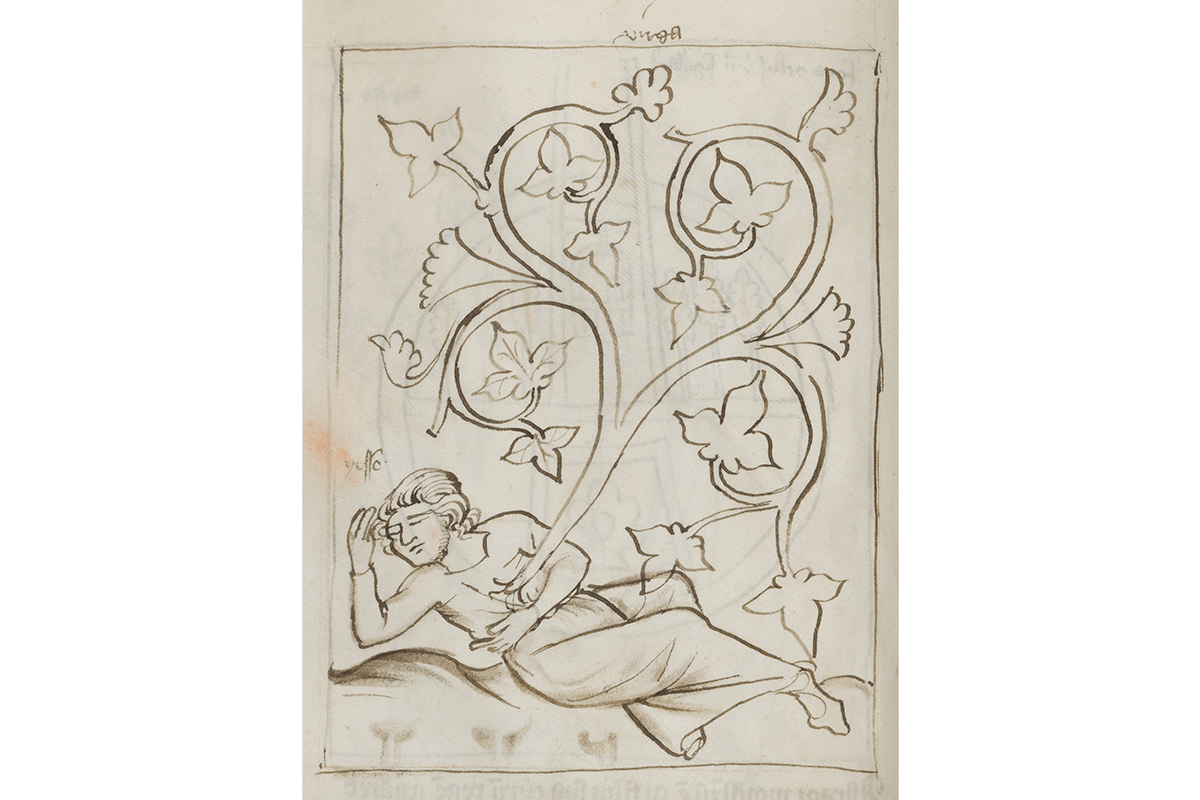

The application of messianic language and imagery to Mary was beyond the pale for early modern Protestants, and unfortunately for the Speculum, Catholics soon turned against it well. The Speculum drew not only upon the Old Testament for its typological examples but also upon a wide variety of history, traditions, and legends from Christian, Jewish, and pagan sources. Sometimes its extrabiblical references are historical, such as Tomyris, queen of the Massagetae, who defeated Cyrus the Great (a type of Mary who defeated Satan). In other instances, it relies on legends and myths. It discusses Codrus, the mythical king of Athens who sacrificed himself for his city, as a type of Christ. In many cases, it augments biblical narratives with extrabiblical tradition, describing the four regions of hell (drawn from Thomas Aquinas’s teaching) and elaborating upon the story of the rejected cornerstone using details of a Jewish legend about the cornerstone in Solomon’s temple.[13]

Although the mixture of biblical and extrabiblical sources, alongside history and myth, was commonplace in medieval Christianity, it came under increasing criticism in the early modern period. Protestant polemics pushed the Catholic Church to reemphasize the centrality of the Bible (over and against other sources), and new standards of historical criticism introduced by Renaissance scholars put additional pressure on inaccurate and implausible tales. Even the biblical exegesis of the Speculum appeared increasingly suspect. Following medieval Christian tradition, the Speculum connects Mary to the messianic prophecy of Isaiah 11—“There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse”—based on the phonetic similarity between the Latin words for shoot (virga) and virgin (virgo). In an age when scholars were painstakingly attempting to reconstruct the earliest biblical Greek and Hebrew texts, such folk etymology and linguistic horseplay appeared dated and embarrassing.[14]

Figure 6: Queen Tomyris beheads Cyrus the Great. Folio 34r. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.

Figure 7: Mary as the “shoot/virgin” from the stump of Jesse. Folio 7v. © Museum of the Bible, 2022. All rights reserved.[15]

As both Protestants and Catholics turned against the Speculum for their own reasons, this once-famous text faded from view in the early modern period. For centuries, though, the Speculum shaped the way many Christians understood the Bible and the history of redemption. Recently, a collaborative project led by Melinda Nielsen at Baylor University and sponsored by the Scholars Initiative at Museum of the Bible completed the first modern transcription and English translation of the Speculum. This critical edition of the Speculum, based on Museum of the Bible’s MS.000321, includes annotations and notes explaining the biblical and extrabiblical references as well as the associated illustrations, finally making this long-neglected text accessible to modern readers interested in the history of biblical interpretation.

Wesley Viner, Associate Curator of Early Modern Bibles and Religious Culture

Notes:

1. Melinda Nielsen, An Illustrated “Speculum Humanae Salvationis” (Brill: Leiden, 2022), 13. All English quotations are taken from the translation available in this volume. The original Latin is available in this volume as well.

2. Nielsen, 29.

3. Nielsen, 374. Image of MS.000321, Green Collection, Museum of the Bible, 4v.

4. Nielsen, 436–37. Image of MS.000321, 35v–36r.

5. Nielsen, 244–51.

6. Nielsen, 438–39. Image of MS.000321, 36v–37r.

7. Nielsen, 251.

8. Nielsen, 251–57.

9. Nielsen, 23.

10. Nielsen, 279–91.

11. Nielsen, 59–61, 235.

12. Nielsen, 430, 432. Images from MS.000321, 32v, 33v.

13. Nielsen, 193–95, 217, 237, 249–51.

14. Nielsen, 54–55.

15. Nielsen, 380, 433. Images from MS.000321, 7v, 34r.